German Repressions against Poles

The Occupier’s Aims

Poles suspected of anti-German positions, i.e., of being members of the resistance movement or of helping the Jews, were persecuted with a particular severity.

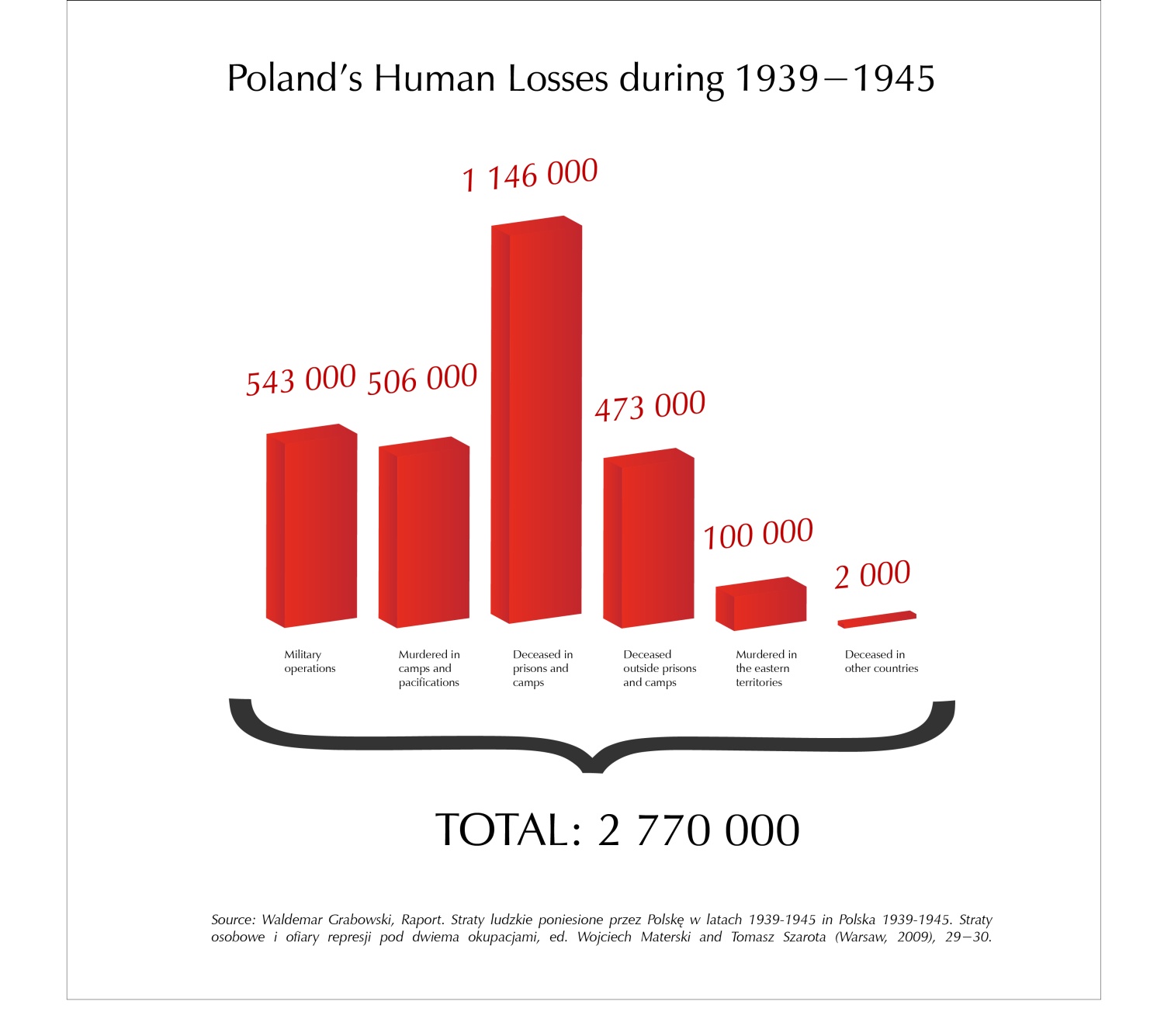

The main aim of German policy in the occupied Polish territories was to totally subjugate the Poles to the Third Reich’s interests. The term ‘Pole’ is understood here in the national or ethnic sense: we discuss elsewhere the prewar situation of people of Jewish, Ukrainian, Lithuanian, or other nationalities who had Polish citizenship.Nazi terror — executions, detention in prisons and camps — was to eliminate the real or potential leaders of the resistance movement along with the nation’s leadership (priests, teachers, etc.), and to force the remain-ing part of Polish society into submission. Poles suspected of anti-German positions, i.e., of being members of the resistance movement or of helping the Jews, were persecuted with a particular severity. Deprived of its elite, the Polish people was to become a cheap, uneducated, and ruthlessly exploited workforce, one which was to labor both in the occupied country and in the Reich. This anti-Polish policy took a heavy toll numbering in the hundreds of thousands of victims. Even many years after the war further thousands of people suffered from permanent physical and/or psychological injuries.

German Crimes against Poles Committed During the Invasion of Poland

This anti-Polish policy took a heavy toll numbering in the hundreds of thousands of victims. Even many years after the war further thousands of people suffered from permanent physical and/or psychological injuries.

From the very beginning of the war, German military operations against Poland were accompanied by crimes committed on Poles. In many places German detachments barbarically shelled and bombarded objects devoid of any military significance. The aim was to cause panic and to crush the morale of Polish soldiers, who were trying to stop the enemy. The destruction of Wieluń near Łódź in western Poland by the German air force (Luftwaffe) became a symbol of such brutal actions, as most of the town’s buildings, including a Catholic church, a synagogue, and a civilian hospital, were leveled. Many other Polish towns and cities fell victim to similar bombardments. German pilots often strafed trains and columns of civilian refugees.

Following the conclusion of the September Campaign the Germans murdered both captive Polish Army soldiers and civilians they found in a range of places thought to be points of Polish resistance.

Following the conclusion of the September Campaign the Germans murdered both captive Polish Army soldiers and civilians they found in a range of places thought to be points of Polish resistance. Special operational units of the German police (Einsatzgruppen) followed the military detachments marching across conquered Polish territory. Their aim was to ensure order in the rear. This was carried out through executions and arrests of the Poles whom the occupier deemed potentially dangerous.

Repressions against Poles during the Occupation

The very first days of the occupation brought far-reaching extermination operations on the Polish territories incorporated into the Reich. These operations were classified and codenamed Intelligenzaktion (Operation Intelligentsia). The occupier’s aim was to exterminate local elites, thus depriving the Polish people of its leaders. The operation’s course was the most horrifying in Pomorze (Pomerania), with the bloody pacification of Bydgoszcz as its symbol. A significant number of Poles arrested in Pomorze lost their lives at the dozens of mass execution sites located for example in Piaśnica near Gdańsk (ca. 14,000 victims), the Szpęgawski Forest near Starogard Gdański (7,000 victims including 1,700 patients of mental institutions in Kocborowo and Świecie), and in the “Valley of Death” near Bydgoszcz. It is estimated that between September 1939 and April 1940 the Germans murdered at least 30,000 Poles in Pomorze. This was not, however, the final number of victims on the Polish territories incorporated into the Reich, for during this same period about 2,000 people were murdered in Poznań, with the executions in Śląsk (Silesia) taking a similar toll. In Łódź and its vicinity the Germans executed ca. 1,500 inhabitants, while in Mazowsze (Mazovia), particularly near Ostrołęka, Ciechanów, and Wyszków the number of victims amounted to nearly 6,700.

The arrests of members of the Polish intelligentsia, conducted before Poland’s Independence Day (November 11, 1939), should be regarded as the beginning of mass repressions inThe General Government. Their aim was probably to prevent possible anti-German activities on that important holiday and to demonstrate the total German domination over the occupied country. In the run-up to November 11, approximately 1,000 people (including university lecturers, high school teachers, judges, lawyers, notaries, physicians, state administration employees, industrialists, members of the leadership of merchant and artisan unions, and Catholic clergy) were detained in prisons and jails where they were beaten and starved. Even though the Germans released the prisoners relatively soon (their absence paralyzed the functioning of hospitals and adversely affected economic life), the last people to regain freedom were released not until a few months later. In Lublin selected prisoners were executed within the scope of this campaign.

In addition to members of Polish social elites, the lists of people to be executed featured political activists, activists belonging to paramilitary organizations, and those accused of possessing weapons or radio receivers.

The November arrests were but an introduction to the great extermination operation conducted against Poles in The General Government in the spring of 1940. The Germans called it Ausserordentliche Befriedunkgsaktion (Aktion AB, Extraordinary Pacification Operation). Its aim was to eliminate those who might play a significant role in organizing and providing support to the resistance movement. In addition to members of Polish social elites, the lists of people to be executed featured political activists, activists belonging to paramilitary organizations, and those accused of possessing weapons or radio receivers. The prisoners were murdered during mass executions, for example in Palmiry near Warsaw, Krzesławice near Kraków, Rury Jezuickie near Lublin, and Firlej near Radom. It is estimated that within the scope of Aktion AB the Germans murdered approx. 6,500 people. Some of those arrested and who managed to avoid execution were sent in mass transports to the Sachsenhausen-Oranienburg and Auschwitzconcentration camps.

Sometimes during pacification operations the Germans murdered all the inhabitants, regardless of their sex or age.

The end of the repressions of the first months of the occupation was not the end of the anti-Polish policy. The German police continually hunted for members of milieux deemed hostile to the occupier, striking hard at the structures of the underground organizations. Not only those arrested on specific charges, but also those arrested only on suspicion of anti-German activities were unlikely to regain their freedom. At first, such a person was detained during the investigation, which usually lasted a number of months. The conditions in prisons were dire. The cells were overcrowded, food rations were pitiful, there was no healthcare whatsoever, and the prison guards incessantly harassed the prisoners. All this was to break the spirit of the prisoner before interrogation. Conducted by security police functionaries, the interrogations involved clubbing, beating with metal bars, and lashing with horsewhips and leather belts. There were special rooms at police stations adapted to this type of “interrogation”. Prisoners might be suspended by their arms from the ceiling or tied to special tables to maximize pain during the beating. It was common at all police stations that some prisoners died during torture or suffered injuries that caused permanent physical disability. Investigations ended with summary trials in special courts. In fact, they were a farce, for the prisoner was forbidden to speak and could only observe the proceedings in silence. In practice, these courts did not give verdicts of not guilty. They simply decided whether a prisoner was to be sentenced to death or sent to a concentration camps for an unspecified period of time.

From 1942, the Germans conducted secret executions less and less frequently. Instead, they began to publically hang their prisoners on gallows placed in important points in Polish cities and towns. Thus, the inhabitants of Warsaw and numerous other cities and towns witnessed many such crimes. As early as the first months of the occupation the Germans’ extermination policy severely hit the peasants, too. Mass operations in the countryside conducted not only by police formations, but sometimes also by military detachments, had two basic rationales. The first one was that peasants supported the resistance movement, particularly the partisan detachments. Equally important was that the Germans wanted to carry out the obligatory levies of crops, potatoes, meat, and other produce imposed on the peasants. These repressions, which affected nearly 800 Polish villages during the occupation, usually involved dispatching a so-called penal unit, which set selected buildings on fire and then murdered usually from 5 to 50 captured inhabitants. Many villages, however, were pacified – that is, all men above the age of 16 were executed or sent toconcentration camps. Women and children were driven out of the village and then all the houses and farm buildings were burnt to the ground. Sometimes during pacification operations the Germans murdered all the inhabitants, regardless of their sex or age. Major crimes of this type were conducted for example in the village of Skłoby and the neighboring villages (April 1940, over 700 victims), Michniów (July 1942 — 203 victims), Borów and the neighboring villages (February 1944 — about 1250 victims, including 300 children) and in Lipiak-Majorat (September 1944 — 448 victims). Moreover, throughout the entire occupation period many Polish peasants fell victim to individual executions, massacres, and beatings conducted by the functionaries of the Nazis’ provincial gendarmerie stations. Aside from the above forms of direct extermination, the Germans also tried to make the living conditions of Poles very difficult, which was another important manifestation of their anti-Polish policy. Those efforts resulted in general poverty, food shortages, lack of healthcare and living space, and slavish work conditions. Many people suffered physical and mental consequences of this situation even many years after the end of the war.

Detailed data on the number of Polish victims during the German occupation are still the subject of research and verification. The minimal number of people murdered or deceased, however, is estimated at 1.5 million men, women, and children.

Repressions for Helping the Jews

The ordinance of the General Government’s Governor-General Hans Frank threatened death to Poles who provided help to Jews, and was promulgated in October 1941. It read: “Jews who leave their designated district without permission shall be subject to the death penalty. Persons who knowingly provide shelter to such Jews are subject to the same punishment. Instigators and helpers are subject to the same punishment as the perpetrator, an attempted act shall be punished as a performed act”. The ordinance was made more specific the following year, when the Germans were liquidating the ghettos and deporting their inhabitants to mass extermination camps. It was restated again that all help provided to Jews (that is, offering them shelter, giving them food, transporting them by any means of transport, buying anything from them) would be punished by death. Capital punishment was to be administered to Poles who knew about a Jew staying outside the ghetto and did not report that fact to the German authorities. In the Radom District the regulation was accompanied by police superintendent Herbert Böttcher’s order to German police stations, which provided that if weapons or Jews were found in a Polish house all persons living there (including children) were to be killed and the house was to be burnt down. Such actions were to serve as a warning to other Poles who might want to help those fleeing the ghettos.

There were many instances of mass executions carried out by the Germans on Polish families who were hiding Jews or giving them food. Many took place in villages whose Polish inhabitants were helping ghetto refugees hiding in the forests. When winter came some decided to shelter them in their houses or farm buildings. The inhabitants of the villages near Cierpielów outside Radom paid the highest price. In December 1942 and January 1943 the Germans carried out a series of executions there murdering over 30 people, including entire families (the Kowalskis, Kosiors and Obuchiewiczes). Over half of the victims were younger than 16. The Germans looted the buildings belonging to those families and then burnt them together with the victims’ bodies. Then the Polish neighbors of the victims were forced to remove the remains from the smoldering ruins. In March 1943 the Germans conducted a similar massacre near the village of Siedliska not far from Miechów in southeastern Poland. The Baranek family of five was murdered for hiding a Jew. But it was the events which took place in March 1944 in the village of Markowa near Łańcut that became the symbol of the fate of Polish peasants who were rescuing Jews. The Ulms decided to hide eight Jews on their farm. After the Germans found out about this, they murdered Józef Ulm, his wife Wiktoria (in the third trimester of pregnancy), and their six small children. All the Jews who were hiding on the farm were also shot. In spite of that massacre, the farmers from the village of Markowa continued to shelter nearly 20 other people of Jews on their farms, and they survived until the end of the German occupation.

After the Germans found out about this, they murdered Józef Ulm, his wife Wiktoria (in the third trimester of pregnancy), and their six small children. All the Jews who were hiding on the farm were also shot

Many Polish city dwellers among the Poles also paid the highest price for helping the Jews. The Wolski family were among them. They built an underground shelter in Warsaw in the garden adjacent to their home. Nearly 40 people of Jewish nationality (the well-known historian and Warsaw ghetto chronicler Emanuel Ringelblum among them) tried to hide there from the Germans. In March 1944 the Germans discovered the hiding place and murdered all the Jews and the Poles who had helped them.

Polish workers often helped Jewish workers in forced labor camp in industrial plants producing for the German army. For example, they gave them food in Częstochowa, Kielce, Ostrowiec, and Pionki thus helping them to keep up their strength and save their lives. The fate of young locksmith Tadeusz Nowak from a plant in Skarżysko-Kamienna became a symbol of those efforts. Captured in April 1943 while passing along some bread to Jews, he was hanged at the plant in the presence of many workers forced to witness the execution. Hanging from the gallows with his hands bound with barbed wire, from Nowak’s neck hung a sign saying “For aiding Jews and delivering letters”.

The exact number of Poles murdered by the Germans for helping Jews remains unknown. The current state of knowledge allows us to estimate that the number was at least 1,000 people. The number of Poles who were sent to jail or prison or to concentration camps for provision of such help was much larger.

The Poles arrested for helping the Jews who managed to avoid execution were usually sent toconcentration camps. Numerous documents proving such measures on the part of the German occupationauthorities have survived in archives. For instance, in 1943 the Germans deported to Auschwitz three inhabitants of Szydłowiec: Wincenty Kołba, Stefan Erbel, and Marian Nazimek, who had probably helped to transfer forged documents to Jews and helped them hide from the Germans. Even though the first two were transferred from Auschwitz to the camps in Buchenwald and Mauthausen, they managed to survive until the liberation. The fate of Nazimek, who was transferred to the Flössenburg camp, remains unknown. The same year the German police arrested a group of Poles from Kozienice accused of hiding Jews. At least two of those people were deported to Auschwitz and then to other camps. Paweł Wachłaczenko survived until the liberation in the Litomierzyce camp (a subcamp of the Flössenburg concentration camp), while Jerzy Burghardt probably died in Mauthausen. Marcin Kowalik, who was “guilty” of helping to deliver a private letter written by a ghetto inhabitant, was murdered in Auschwitz in 1943. These are just a few names from a long list of prisoners.

The exact number of Poles murdered by the Germans for helping Jews remains unknown. The current state of knowledge allows us to estimate that the number was at least 1,000 people. The number of Poles who were sent to jail or prison or to concentration camps for provision of such help was much larger.